Achieving The Triple–

By Dr. Alpesh N. Amin

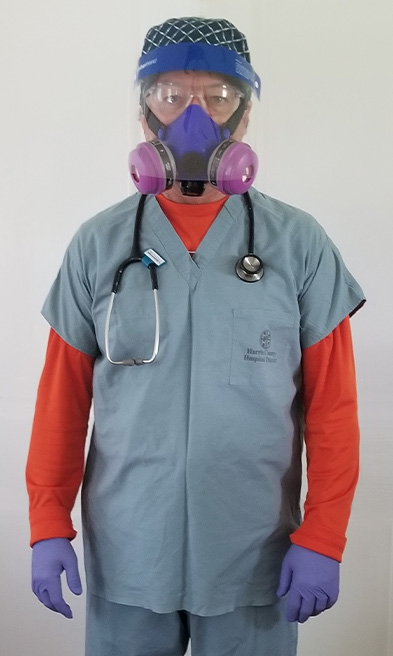

Hand hygiene is a proven safety practice in health care. Unfortunately, hand hygiene is underperformed on a routine basis, leading to the transmission of pathogens and spread of infection from patient to patient. Similarly, stethoscopes – the clinician’s third hand – pose the risk of carrying pathogens and spreading infection from patient to patient. Like hands, stethoscopes can be effectively decolonized using alcohol. Yet, despite effective means to decolonize stethoscopes, our study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine showed only 16% of physicians or student trainees employed stethoscope hygiene prior to patient contact.1 In non-isolation rooms, the issue was exacerbated – we found only 4% of patients received care involving stethoscope hygiene.1

As patients are alarmingly exposed to unclean stethoscopes, stethoscope transmission of pathogens from patient to patient can undermine the efforts of hand hygiene programs. Effectively promoting hand and “third hand” hygiene best practices could reduce infection rates. In turn, infection control can decrease healthcare costs (including reducing antibiotic use and complications) while improving the patient experience – cornerstones of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Triple Aim”.

An easy to use and fail-safe method that improves stethoscope hygiene could help facilitate achieving the Triple Aim.

1. Jenkins IH, et al. Low Rates of Stethoscope Hygiene. J. Hosp. Med 2015;7;457-458.

Alpesh N. Amin is Professor of Medicine at the School of Medicine, Chair of the Department of Medicine, and Executive Director for the Hospitalist Program at the University of California, Irvine. He specializes in hospital, internal and perioperative medicine with research interests including patient care and quality improvement in the acute setting.

Third Hand Vector series spotlights the clinician’s third hand and the risks that contaminated stethoscopes pose to clinicians, patients and healthcare systems. The series features leading experts in infection control, patient care and quality measures raising awareness of the importance of aseptic barriers in reducing transmission of infectious diseases.

Connect with Us